Virtual Finality Gadget

The Virtual Finality Gadget (VFG) is a programmable finality mechanism that grants each application on KIRA the ability to establish its own verification and consensus rules. It divides application logic into execution (operated by Executors) and verification (overseen by Fishermen) components. VFG allows developers and users to customize their finality logic, such as choosing an optimistic model of execution (rollups - valid by default), pessimistic (rolldowns - invalid until verified), or any bespoke verification logic, even allowing for the creation of recursive appchains and human judgment by a defined set of network actors. VFG’s ability to support non-deterministic verification binaries makes it particularly useful for complex, blockchain-less, Web2-scale applications, such as AI and gaming as well as makes it impossible for an attacker to predict if his attack attempt would be successful as the verification rules can be customized by each Fisherman individually and remains private.

How It Works

In KIRA, RollApp are simply packaged binaries within Docker containers. This ensures security by isolating RollApp from the host OS to prevent malware risks and enabling precise management of resources like CPU, GPU, RAM, and disk space per each individual application.

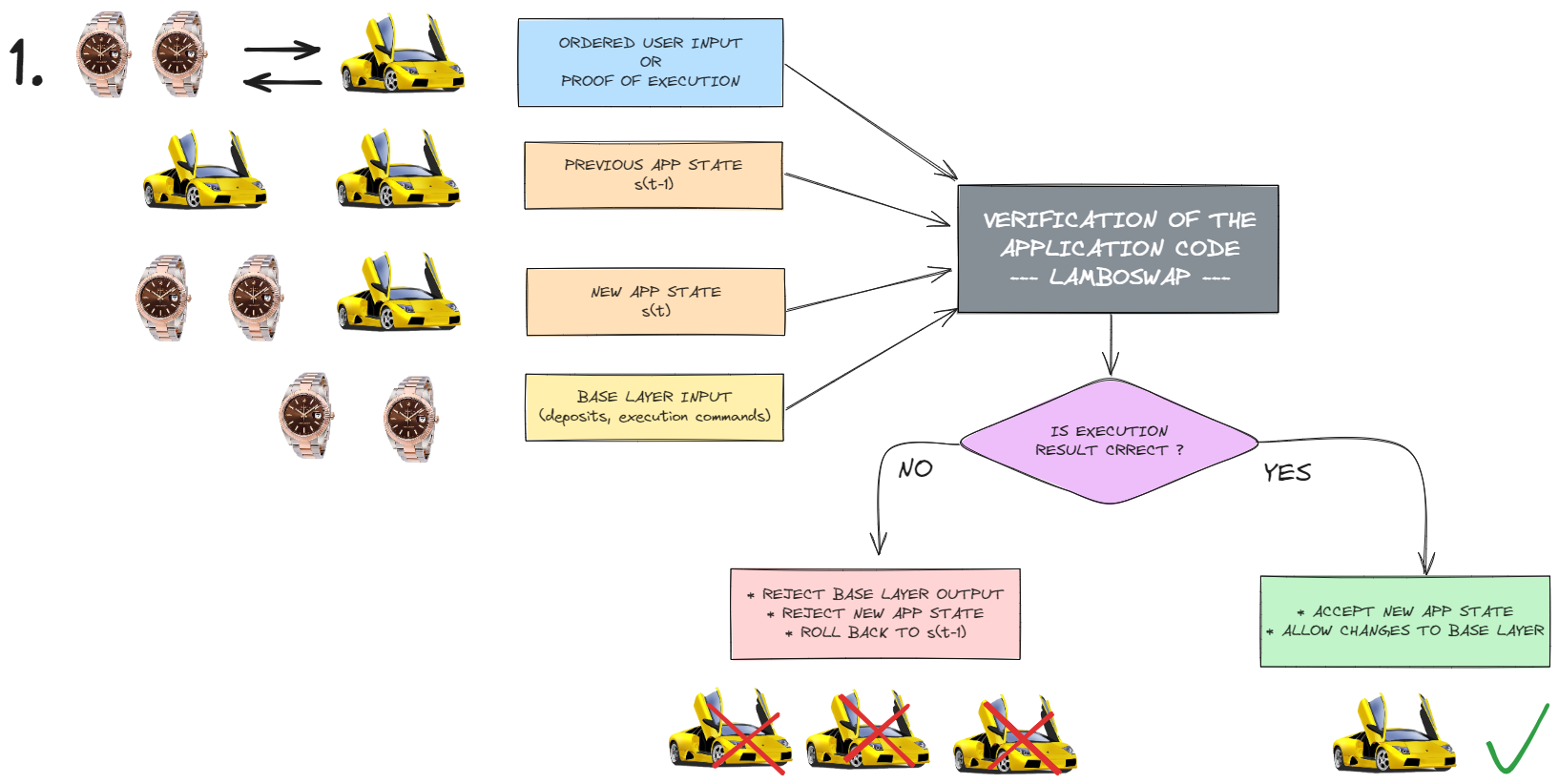

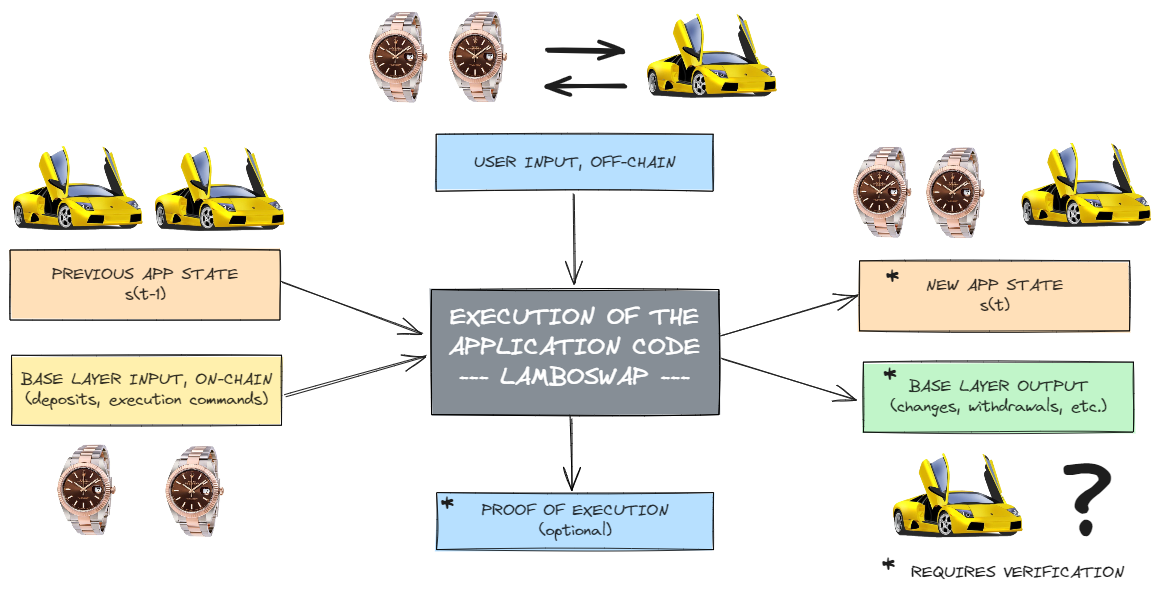

Each application is architecturally divided into two distinct components: the execution logic and the verification logic, each encapsulated within its own Docker container. The execution logic container, managed by Executors, is responsible for running the application's code such as state machine or zkVM, while the verification logic container, overseen by Fishermen, assesses the integrity of the RollApp state changes that Executors submit to the KIRA base layer, SEKAI.

From a high-level perspective, Docker containers are executed and monitored by Consensus nodes within KIRA, facilitated by RYOKAI for operational management and coordination. The containers interact with the network through local INTERX nodes (serving as decentralized APIs or DAPI/DA) and SEKAI nodes (connecting to the KIRA blockchain), ensuring seamless integration and communication within the ecosystem.

The role of the execution container is to accept input sequenced by INTERX into one of the ports and execute commands from that input according to the code embedded within the container. Since there might be many executors (Multi-Party Computation) one of them is round-robin elected as leader who can then publish state root - publishing the hash of the new app database state and proposing changes to dApp account balances on the KIRA base layer. The application lifecycle has a form of forever changing states (sessions) from one KIRA base layer block to another proposed by a single leader. The proposed changes must then be approved by the verifiers through a process in which a threshold of approvals must be reached. If even a single Fisherman disagrees with the state transition the app is stopped and KIRA governance steps in to resolve the issues.

The VFG does not enforce any specific way of evaluating the shift from one application state to another. Instead, it empowers developers and all who participate in the verification of the application execution process to customize the method in which a binary verification outcome is produced — either 'yes' or 'no' — to affirm or challenge the transition's validity. This approach presents a strong contrast to current rollup systems, where the verification process relies on an execution binary or container that must remain identical and public among all Executors of a specific application. In the case of the verification container, although a single shared and public version must be provided by developers, possible bounties for catching issues provide an additional economic incentive for Fishermen to customize the verification container.

We have to assume that in the future there will always be better and more efficient ways to trustlessly verify computations. Today that might be something as simple as re-execution or zkVM and using GPUs to generate ZK proofs. Tomorrow, it might be something completely different. The VFG protocol was created so that application developers can long-term support their applications without being locked into a single framework or protocol. Our intention is also to signal that Fishermen should not blindly trust developer teams, especially in an era of ever-present bugs and stegomalware. These can turn even seemingly deterministic code into unpredictable chaos, against which no one has yet proposed a reliable method to protect users from.